Postcards from Chiang Mai

Postcards from Hanoi

Postcards from Ha Long Bay

Postcards from Ninh Binh

Postcards from Sapa

Food tour of Hanoi

My favorite thing in Vietnam

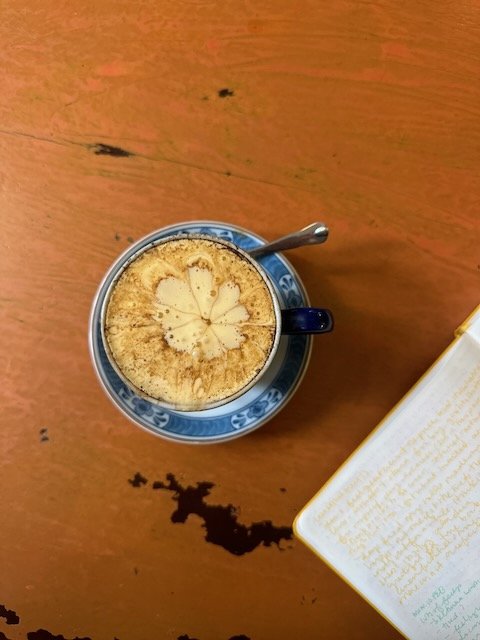

Is all coffee “Vietnamese coffee” in Vietnam?